Cow’s milk allergy is the most common type of food allergy in children—it’s also the weirdest.

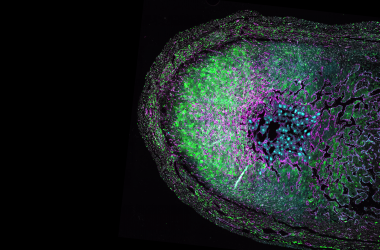

In all allergies, a person gets sick when immune cells overreact to normally harmless molecules, such as milk proteins, peanut proteins, or cat dander. Immune cells think the offending molecules are dangerous pathogens, and they launch a counterattack. The immune cells churn out inflammatory molecules, and a person begins to get very, very ill.

Most food allergies last a lifetime. Cow’s milk allergy is strange because kids usually “outgrow” it. In fact, around 80 percent of children with a cow’s milk allergy see the allergy disappear by adulthood.

At La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI), scientists are taking a closer look at how immune cells drive allergic reactions. Their research may guide the development of better diagnostics and therapies for cow’s milk and other food allergies.

LJI Postdoctoral Fellow Sloan Lewis, Ph.D., is leading an innovative new study into cow’s milk allergy with funding from the Institute’s Tullie and Rickey Families SPARK Awards program, via the Rosemary Kraemer Raitt Foundation. Dr. Lewis wants to know how a subset of immune cells, called monocytes, responds to milk proteins in children with cow’s milk allergy. Her goal is to see whether monocytes can reveal an “immune signature” that might help doctors diagnose cow’s milk allergy quickly and accurately.

“We do have non-invasive diagnostic tests for allergens, and they can work decently well, but they’re not very reliable. There are a lot of false positives and false negatives,” says Dr. Lewis.

Doctors often begin allergy testing with a titer test, which analyzes the blood for antibodies specific for different foods. Some patients also endure skin prick tests, where doctors prick the skin to expose patients to different allergens to see how they respond.

“The gold standard diagnostic method right now is the food challenge,” says Dr. Lewis. “Doctors give kids whatever they’re allergic to and they see what happens to them—and obviously this is horribly stressful, super expensive, and high risk.”

Dr. Lewis thinks food allergy tests could be much more precise and a lot less risky. Her work in cow’s milk allergy started with a project in the laboratory of LJI Professor Bjoern Peters, Ph.D. The team worked with scientists at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, Johns Hopkins, and the University of Southampton to collect blood samples from children with cow’s milk allergy.

The researchers then studied how T cells in these samples responded to proteins in cow’s milk and tracked down which proteins sent T cells into attack mode. Drs. Peters and Lewis then compared T cell responses from these patients to T cell responses from pediatric patients with other food allergies—but not milk allergy.

This investigation revealed T cell characteristics only seen in kids with cow’s milk allergy—an immune signature that may prove useful in designing a future diagnostic. [Read the study]

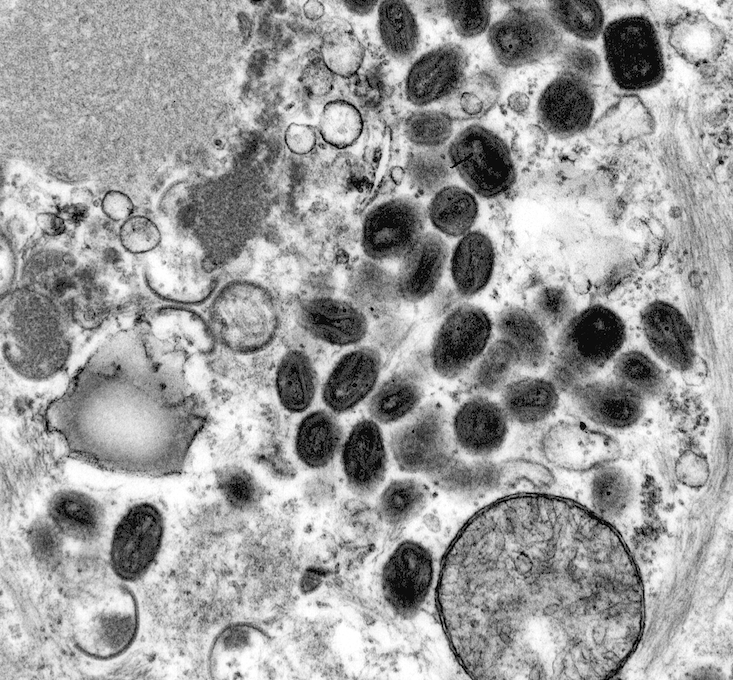

Before she worked with T cells, Dr. Lewis was a monocyte expert. Monocytes are fascinating cells because they are part of the innate immune system, the body’s first response against disease. Rather than fighting a pathogen directly, monocytes ring the alarm bells and call T cells to the battlefield. Monocytes might also fuel food allergies by mistakenly sounding the alarm

against certain proteins in foods.

“A few studies have hinted that monocytes and other kinds of innate immune cell populations are involved in food allergies,” says Dr. Lewis. “But there’s not a lot known about monocytes in cow’s milk allergy.”

So Dr. Lewis had to start at the very beginning. Her first question is whether the donor blood samples (the same ones from the T cell study) contain more or less than the normal amount of monocytes. In short—are monocytes doing anything weird inside these kids with cow’s milk allergies? Answering this type of fundamental immune system question may help researchers finally understand how food allergies develop and why some disappear over time.

Dr. Lewis also hopes to shed light on immune signatures related to subtypes of cow’s milk allergy. For example, some children allergic to liquid cow’s milk do just fine when cow’s milk is baked into a food. “There are also kids who are allergic to both, and they do not grow out of it,” says Dr. Lewis. That distinction would be important for caregivers, doctors, and kids to know as early as possible.

In the end, Dr. Lewis hopes this research may offer a better way to diagnose and treat many different food allergies.

“It was eye-opening for me when I started talking to people about this research,” she says. “So many people are affected by food allergies. The prevalence is surprising—and clinicians are very interested in what we find.”

Watch: Sloan Lewis, Ph.D., discusses her SPARK-funded mission to learn more about dairy milk allergy.