For centuries, smallpox ruled the world. Smallpox struck down pharaohs and helped fell the Roman Empire. A young Queen Elizabeth I barely survived the illness—though she bore pox scars for the rest of her life. Some called the disease “the speckled monster.”

As the centuries rolled along, early doctors in Asia, India, and Europe chanced upon a promising smallpox treatment. They found that exposing a healthy person to a scab from a person with smallpox could protect that healthy person from getting sick…somehow?

No one knew about immune cells yet, let alone viruses, so the procedure remained very mysterious—and very risky.

Then in 1774, an English farmer named Benjamin Jesty noticed something strange about the milkmaids in town. Despite a raging smallpox epidemic in his area, the milkmaids stayed healthy. These milkmaids had previously contracted a disease called cowpox, a milder sort of “mini smallpox.” He wondered if these earlier cases of cowpox somehow protected them from smallpox too.

In 1796, an English doctor named Edward Jenner took this hypothesis further by purposefully injecting cowpox-infected tissue into a healthy patient. Despite Jenner’s dubious research ethics (his first patient was an 8-year-old boy), he proved that cowpox exposure could indeed protect a person from smallpox. This inoculation is thought of as the first modern vaccine, and the term “vaccine” even holds a bit of this history: “vaca” means cow in Latin.

Jenner’s breakthrough led to much more sophisticated vaccines against a huge range of diseases. By 1980, the World Health Assembly declared the smallpox eradicated across the globe.

The story of cowpox and smallpox is also important because it illustrates a phenomenon called immune cell cross-reactivity.

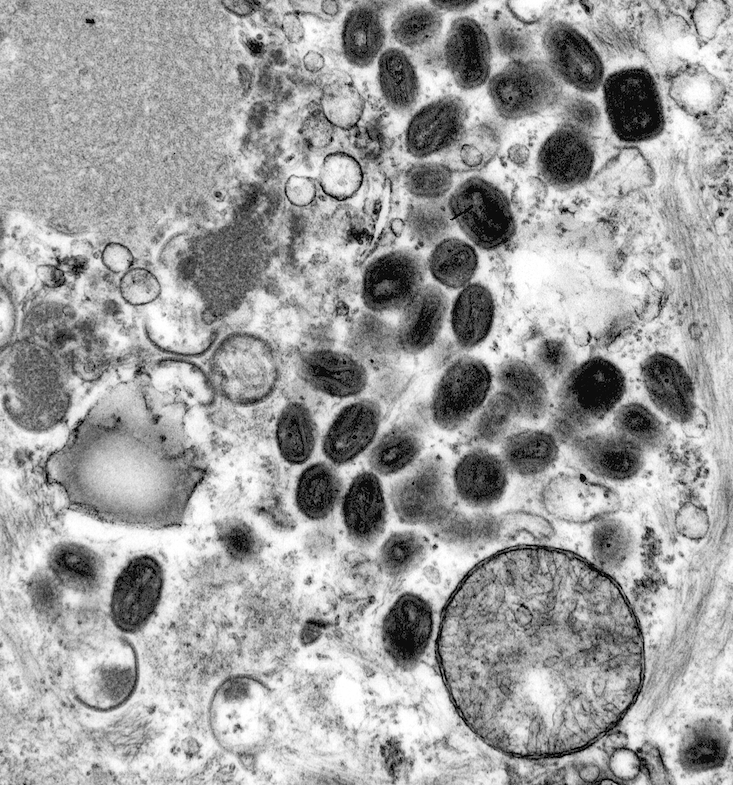

Immunologists today understand that cowpox (caused by cowpox virus) and smallpox (caused by variola virus) are both members of the Orthopoxvirus genus of viruses. These closely related viruses share a physical resemblance. They’re Liam and Chris Hemsworth: if you’ve seen one, you’ll see the resemblance in the other.

Immune cells that encounter cowpox can learn to recognize and target smallpox at the same time.

Immunologists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) are working to exploit immune cell cross-reactivity to fight emerging pathogens. During the COVID-19 pandemic, LJI scientists published the first studies demonstrating that people who had previously caught a common cold coronavirus had lingering T cells that responded to SARS-CoV-2. These T cells had never seen the novel coronavirus before, but they remembered seeing something like it.

Viruses are smart, but scientists are smarter. Which other viruses can we “trick” the immune system into fighting off with cross-reactive cells?

Learn more in our latest Immune Matters cover story: Delivering better vaccines.