La Jolla Institute for Immunology’s (LJI) newest faculty member is on the hunt for unicorns. Since joining the Institute in June, he’s been looking for the strange (his word) sorts of immunologists eager to use tools in computational biology and physics to study how the body fights disease.

“I’ve always been a computational unicorn inside of experimental labs,” says LJI Assistant Professor Tal Einav, Ph.D. “And it’s always been a wonderful experience. But starting my own group at LJI will be my opportunity to put together a fully computational lab where all the unicorns can come together.”

It’s a bit surprising that Dr. Einav even ended up in immunology. “My background was pretty weird from the get-go,” says Dr. Einav. For example, after majoring in physics at Rice University, he had no idea which professors he wanted to work with during graduate school at Caltech. So he asked every professor for a 15-minute meeting to discuss their research.

“I let science take the backseat, and I primarily searched for the best possible fit in personality. Then I met this really cool professor, Rob Phillips, Ph.D., working in biophysics,” says Dr. Einav. “He told me, ‘Physics has some of the greatest tools, but biology has some of the greatest problems. Why don’t you come work with me in this new area?’ And so I did.”

As a Ph.D. candidate in the Phillips Laboratory at Caltech, Dr. Einav discovered the power of computational biology—the idea of using data science to understand living things. He began by working with Dr. Phillips to study cell biology, namely, how bacteria read their genomes and make different proteins.

Dr. Einav loved his Ph.D. work. He loved the lab environment at Caltech. So, of course, he decided to do the unexpected thing. He left school for a year. “Most people take a break between undergrad and grad school, but I took a year off in between years of graduate school,” he says. “For that year, I worked as a programmer in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois.”

Champaign and Urbana are sister cities in central Illinois. The big draw is the University of Illinois, which Dr. Einav wasn’t a part of. Though he did dive into one campus activity: dance. Dr. Einav had found a passion for swing dancing as a sophomore at Rice University. The push and pull of dancing with a partner made sense to the theoretical physicist in him. “As nerdy as it sounds, I interpreted the whole thing as applied classical mechanics,” he says.

Dr. Einav started off taking classes in the more traditional East Coast swing style, and within a year he was dancing 10 hours a week. Three years later, he decided to dive into West Coast swing dancing without taking any classes. “It was a rough transition—just purely trial by fire,” he says. “But West Coast is more free form, and I loved it.”

Dr. Einav was eager to continue dancing in Champaign-Urbana when he happened to see a hip hop group perform at a campus fair. He asked if he could audition for the group. “They said, ‘No problem. If you’re a dancer, you belong with us,’” he says. “It was a blast.” He kept dancing once he returned to complete his graduate studies at Caltech, where he ended up teaching weekly hip hop dance classes.

Meanwhile, Dr. Einav was exploring his second passion: immunology. By the end of graduate school, Dr. Einav was working with Caltech biochemist Pamela Bjorkman, Ph.D., to study how to design better antibodies against HIV. “Not only could I make a difference on this deadly disease, but the research demanded the full range of my skills,” says Dr. Einav. “It involved an intimate combination of biology, physics, math, and numerics.”

He felt that he had to stay in the immunology world after graduation—as the oddball lab member who manned a computer rather than a lab bench. With his doctorate in hand, Dr. Einav joined the laboratory of Jesse Bloom, Ph.D., at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle.

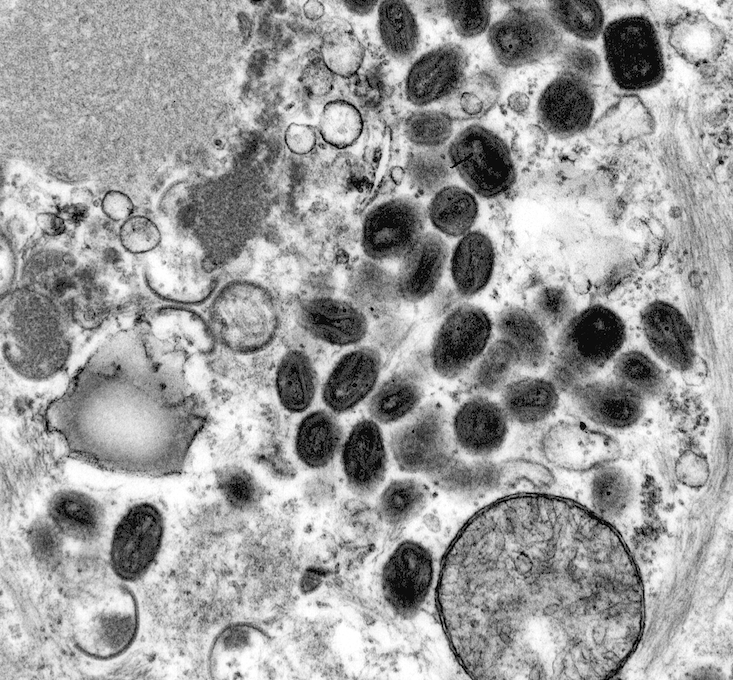

Dr. Einav’s work in computational biology comes at a fascinating time in history. Thanks to advances in genetic sequencing and new ways to zoom into single immune cells, researchers today are taking a closer look at human immune responses than ever before.

Put very, very simply, this technique is a bit like assembling a jig-saw puzzle. Get enough pieces in place, and you can predict what the missing pieces will look like. “I listened to this explanation and thought, ‘There is no way that something like this could exist,’” says Dr. Einav with a laugh. “But I sent him a dataset, and he showed me the magic.”

“We have these tremendous datasets that we’re just barely tapping into,” says Dr. Einav.

Still, the world is vast, and even massive datasets cannot capture every detail. A pivotal moment in Dr. Einav’s career came just as he finished giving a presentation on his work. A colleague came up and asked if he’d tried a computational method called “matrix completion.”

“We have these tremendous datasets that we’re just barely tapping into.”

LJI Assistant Professor Tal Einav, Ph.D.

Dr. Einav quickly realized the potential for using matrix completion to fill gaps in disease-related datasets. In a pivotal Cell Systems paper, Dr. Einav showed how the technique can help immunologists predict new viral behaviors. “I was really proud of that paper,” says Dr. Einav. “That’s how I first got into machine learning in immunology.”

His research at Fred Hutch demonstrated the surprising ways computational biology can help us beat disease, and this work also won him a prestigious Damon Runyon Quantitative Biology Fellowship.

At LJI, Dr. Einav plans to initially study the immune response to the influenza virus. He hopes his laboratory can pave the way for a fundamentally new form of personalized medicine.

“Can we use big datasets to extract general principles about how we respond to vaccines, and then modify our current one-size-fits-all mode of vaccination to create personalized vaccines?” Dr. Einav asks.

For example, by uncovering important patterns in the human immune response, he hopes to figure out what works best for specific patient groups—from the young to the elderly, from healthy people to individuals who are immunocompromised.

Dr. Einav is far from the only LJI “unicorn” making a space for computational biology in immune system research.

Fellow faculty members Professor Bjoern Peters, Ph.D., and Associate Professor Ferhat Ay, Ph.D., specialize in data science and the development of computational tools. The Institute is also home to the Human Immunology Project Consortium (HIPC) Data Coordinating Center and to extremely valuable, open access databases such as the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB), led by Dr. Peters and LJI Professor Alessandro Sette, Dr.Biol.Sci., since 2003, and the Database of Immune Cell Epigenomes (DICE), led by LJI Associate Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand, M.D., Ph.D., since 2014.

All of these efforts mean that a tremendous amount of data flows through LJI, providing ample opportunities for computational biologists like Dr. Einav to collaborate and extend the impact of their work.

Dr. Einav is also keen to work with researchers from the Saphire Laboratory and the Shresta Laboratory to study Ebola virus, dengue virus, and other pathogens. He says he knew early on that LJI would be a good home for his unique brand of science.

“I deeply resonated with the spirit of the faculty and the flavor of research being done at LJI. The big questions they’re asking are the same questions I’ve been going after,” says Dr. Einav. “When you find that fit, it’s incredibly invaluable.”

Watch: Assistant Professor Tal Einav, Ph.D., shares his research at La Jolla Institute for Immunology’s “Life Without Disease” event on Oct. 4, 2023.

“The kinds of vaccine studies we’re doing these days are really cool,” says Dr. Einav.