Dr. Myers speaks with the drawn-out vowels of someone who came of age in 1990s SoCal. He’s the kind of scientist who rides a bicycle to work. He marks milestones not with plaques on the wall but with tattoos. “My lab members know my offer—when they publish a paper, I will pay for a scientific tattoo if they want it,” he explains. His move back to Southern California was a homecoming.

After completing postdoctoral training at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass., Dr. Myers joined LJI as an Assistant Professor in April 2021 and launched the Laboratory for Immunochemical Circuits.

“I’m trying to build and map these very complex signaling-to-transcription networks—so basically how cells interpret their environment and process that information to turn on or off the genes they need to respond correctly,” says Dr. Myers.

Dr. Myers has been part of LJI for two years now. He’s organized his lab space, gotten new machinery up and running, and hired a crew of lab members. None of that has been easy, especially amid global supply chain problems.

STEP ONE: MOVING IN. Dr. Myers’ laboratory is sandwiched between the laboratories of LJI Professors Anjana Rao, Ph.D., and Patrick Hogan, Ph.D. From one side of the long room you can see how several sections of lab benches are split between the three faculty members. Dr. Myers appreciates the chance to work alongside Drs. Rao and Hogan. Both scientists are experts in protein signaling and have welcomed new collaborations with Dr. Myers.

Staff in LJI’s Facilities Department helped Dr. Myers make the space his own. “This office actually used to be the break room, so I was making friends right from the start,” he jokes. Besides the new desk and white boards, it still kind of resembles one. It’s a surprisingly large room with a couch along the wall.

Dr. Myers keeps bottles of hot sauce and salad dressing on his desk and a mini fridge in the corner by the window.

Research isn’t just a vocation for Dr. Myers. Twenty years ago, he was an art student at a community college. Then he took a human biology course and discovered he loved science—and he was good at it. He loved learning about the complexity and the chemistry behind the ways cells signal each other.

“I’m very passionate about this. I feel like it’s my job and my hobby,” he says. “I love thinking about it. I wish it didn’t keep me up at night, but I love the fact that there’s always something new and exciting, and I don’t mind being a little obsessive.”

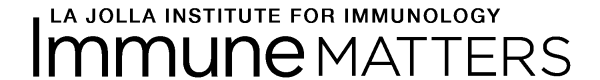

STEP TWO: GETTING THE GEAR. Mass spectrometers are workhorses of protein signaling and biochemistry. These complex instruments allow researchers to identify unknown proteins in a sample. Just as a bird watcher needs binoculars, a biochemist needs a mass spectrometer. To do any proteomics research in his new space, Dr. Myers needed a mass spectrometer that costs about $1.4 million. Thanks to the generosity of an anonymous donor, Dr. Myers made this key purchase fairly early on. “I am so grateful to this donor,” he says. “This funding allowed me to build the mass spectrometry facility of my dreams from scratch, with everything we need. And it’s arguably one of the most sophisticated mass spectrometry and proteomics platforms on the Mesa.”

Dr. Myers and his lab members are experts at troubleshooting the mass spectrometer when something goes wrong. As Dr. Myers explains, this equipment is often out of commission due to the intense nature of his work. “We don’t have to be running at this high level of sensitivity but to answer the questions we want to, we do,” he says. Running at the limits of what the mass spec can do means new insights but also more challenges in the process.

From there, he needed to order the accessories (special columns, tiny glass capillary tubes, etc.) to actually use the machine—things an immunology institute typically does not have. As the Institute’s facilities team worked to assemble the lab infrastructure, Dr. Myers was stuck in limbo. Basic lab supplies have been in short supply due to the pandemic, and his orders took months to arrive at the Institute. “I was waiting on this last piece of the system, a speed vac, which is this centrifuge that applies a vacuum so we can remove acids and solvents from samples,” says Dr. Myers.

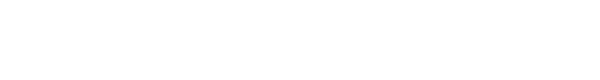

“Every month the company told me it would come the next month. Finally, it came in after seven months, and then it didn’t even have the tube I needed. I had to go to a hardware store in Carmel Valley to get the right tube.

“In fact, we only recently got the right part number for proper tubing. But once that last piece was here, we were sailing.”

STEP THREE: ASSEMBLING THE TEAM. “The risks of starting a new lab are manifold and stressful,” says Dr. Myers. “Not only do I have to be good enough to do the work, I have to be good enough to train people who aren’t experts yet,” he says. “Their careers are kind of in my hands.”

The first person to take the leap was an undergraduate student named Patrick Kennedy. Kennedy impressed Dr. Myers with his persistence and patience in the lab’s early days. “He got a lot done over that first summer when we only had a set of half-broken pipettes,” says Dr. Myers, who ended up hiring Kennedy to stay on as a full-time research technician. The full set of pipettes also took seven months to arrive, he notes. Dr. Myers also feels lucky to have found Research Technician Cindy Manriquez Rodriguez. “She’s great!” he says. “I think she learned maybe three mass spectrometry data analysis software programs in one week.”

His laboratory now has five full-time members, with one on the way, and hosts several students and interns. His trainees include Postdoctoral Fellows Khanh Nguyen, Ph.D., and Maria Matias, Ph.D. “Khanh has done a fantastic job keeping the mass spectrometer running at a high level,” he says. “And Maria has done a great job setting up our mouse work and immune cell purification protocols. She’s a T cell biologist, so she has a lot of experience that I don’t have.”

The last two years of work are starting to pay off. In 2022, Dr. Myers received a grant of over a million dollars from the NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences that funds part of his laboratory’s vision. This grant is a major milestone in the life of a new lab, and the funding supported research that led to a major paper for the Laboratory for Immunochemical Circuits. Dr. Myers is also listed as last author among the study contributors, which designates him as a study leader.

The research, co-led by Dr. Rao, helps solve the mystery of why an enzyme called OGT is critical for cell survival. This study came out in a top scientific journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and has implications for treating cancers, metabolic diseases, and more.

For his first, first author paper of his career, Dr. Myers got a tattoo of a boxing baby with a piece of mass spectrometry equipment for its head. His next tattoo will commemorate his move from Boston to San Diego.

“There are these old sailor tattoos where you got a clipper ship on your chest,” says Dr. Myers. “I was going to pick the fastest clipper ship that sailed from Boston to San Diego. It was actually called the Eclipse, the HMS Eclipse, and the name of our mass spectrometer is also the Eclipse. So that’s the plan.”

Interviews by Matthew Ellenbogen and Madeline McCurry-Schmidt

Article by Madeline McCurry-Schmidt

Photos and video by Matthew Ellenbogen