The naturalist E.O. Wilson once wrote, “Fascination creates preparedness, and preparedness, survival.”

And is there anything more fascinating than a pathogen? They mutate into endless forms. They twist and collapse and morph their very beings as they infect their hosts.

Scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) have the tools to dissect the many ways pathogens try to slip into our bodies and discover how the equally wonderous human immune system fights back. Every day, these researchers learn more about how we can combat the next pandemic.

An eye on emerging threats

Pathogens don’t come out of nowhere. LJI scientists have shown that better understanding past outbreaks can help us fight future threats.

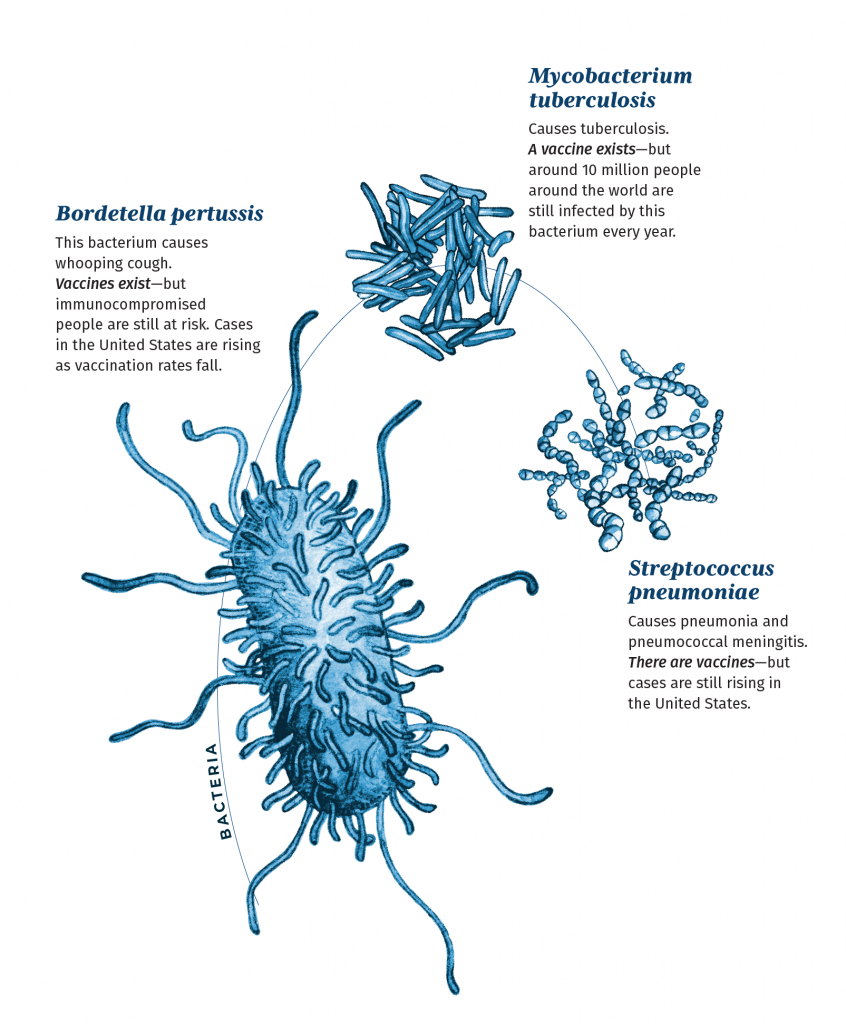

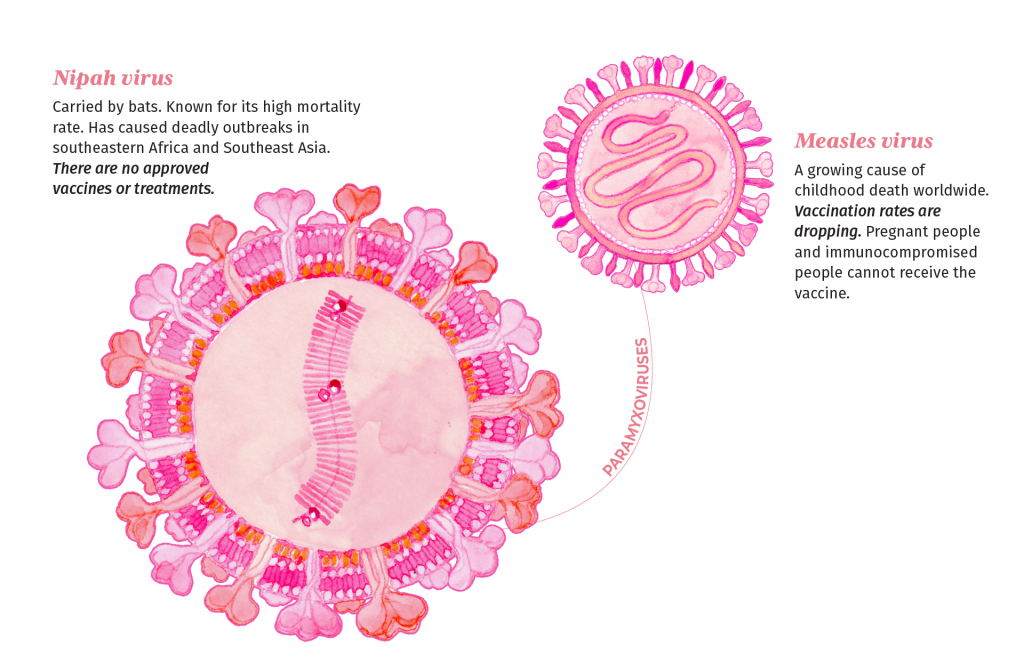

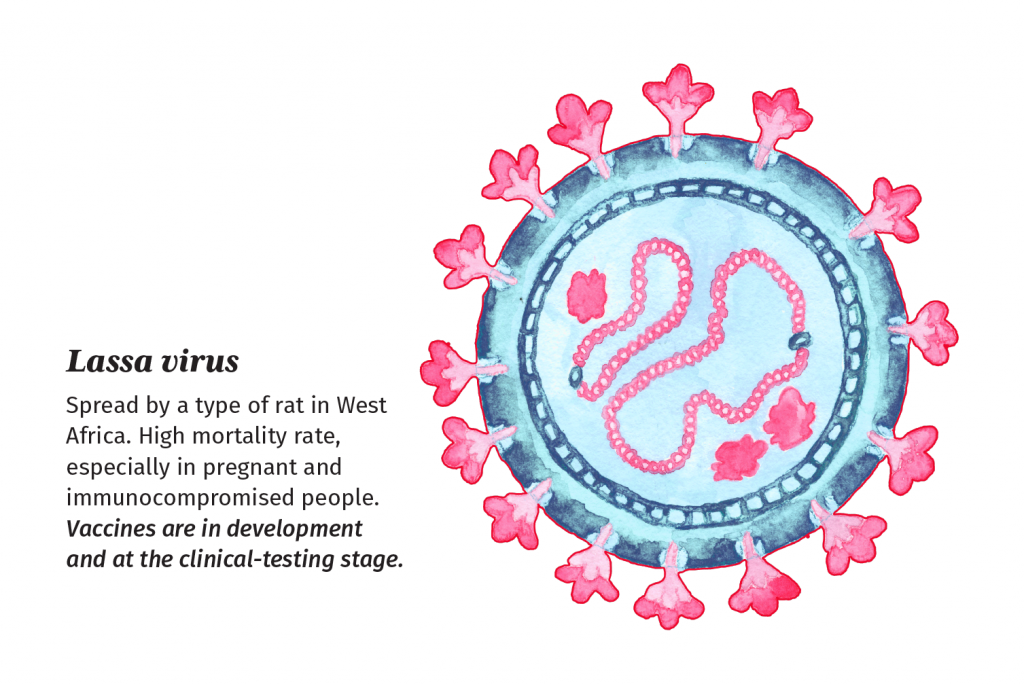

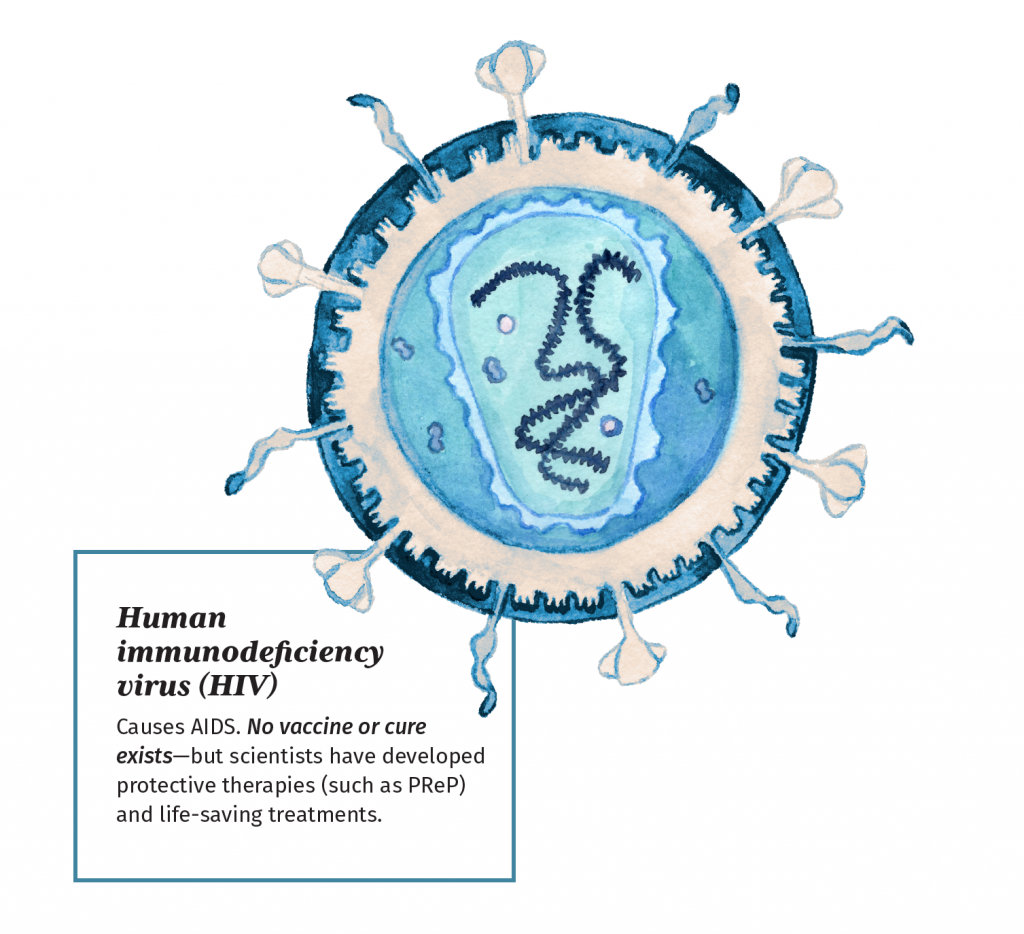

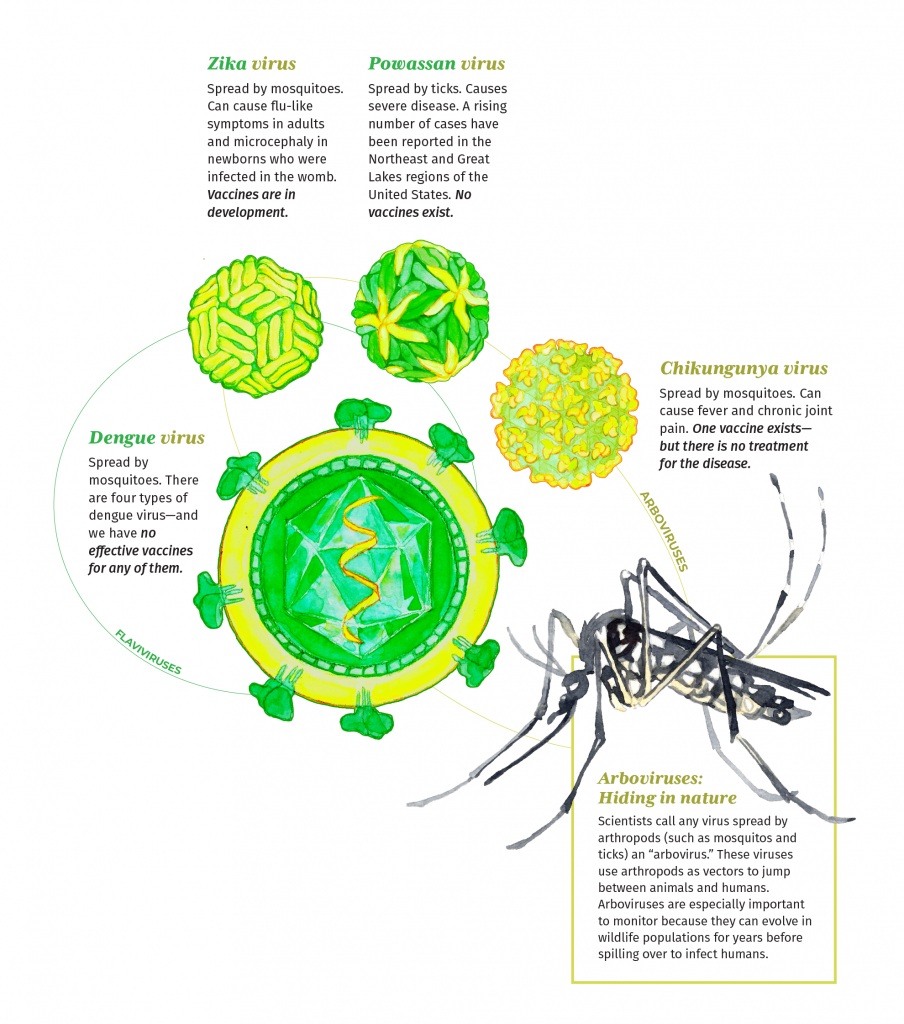

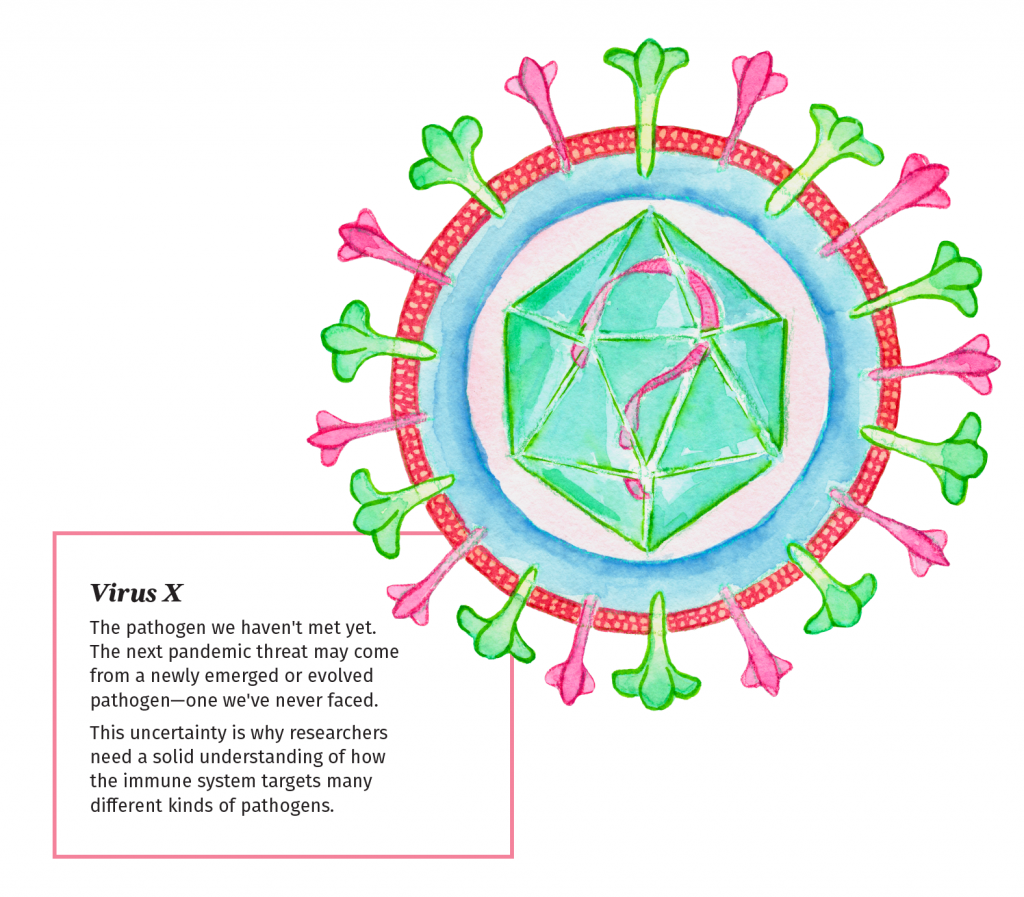

Since 2019, we’ve discovered so much about how the immune system responds to coronaviruses. But there are many more deadly pathogens out there—and new threats can “spill over” from wildlife populations at any time.

LJI scientists work closely with international partners to monitor these emerging diseases. By combining experimental studies with computational work, researchers have uncovered how specific immune cells handle these diseases.

These insights are crucial for developing vaccines that teach the body how to ward off severe infection.

Learning from past pandemics

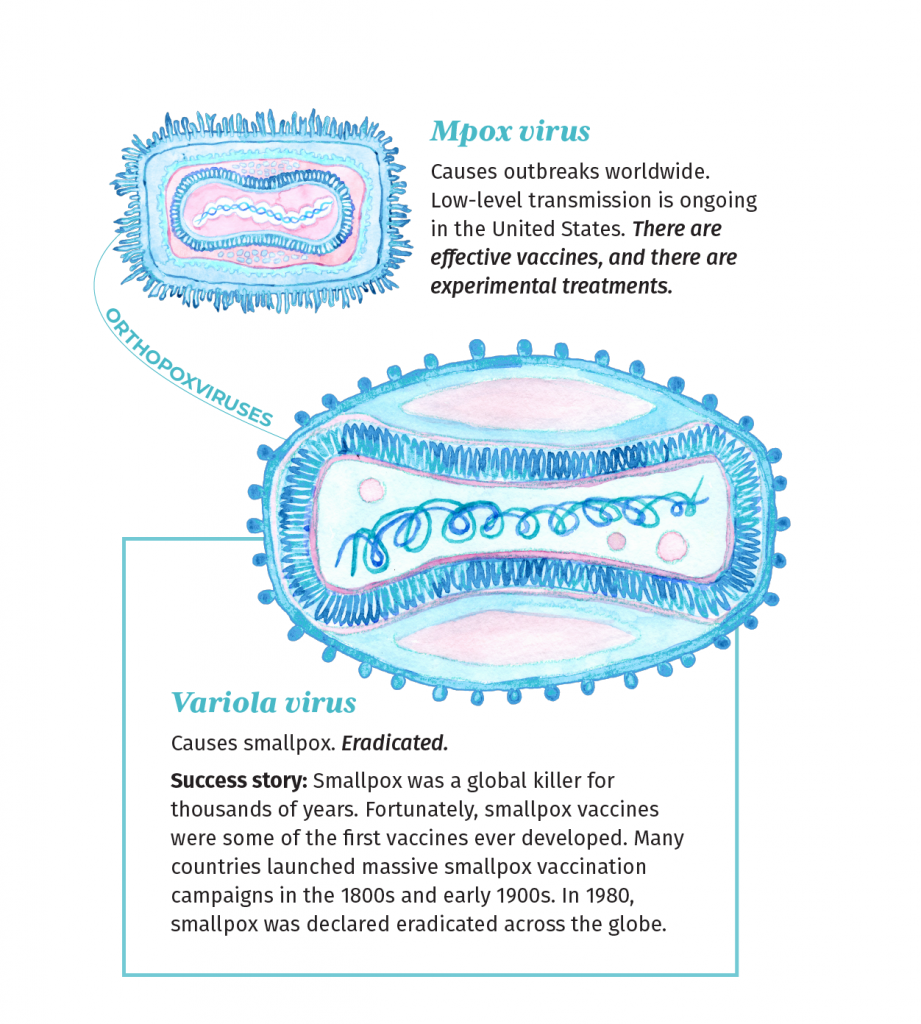

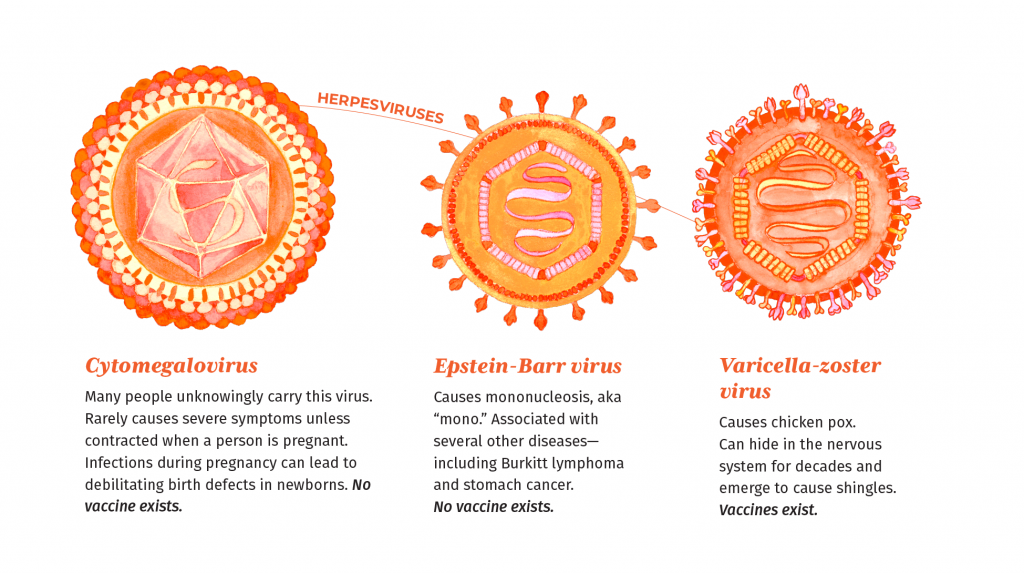

LJI scientists are investigating how the immune system fights different members of the same family of pathogens. Spotting these “family resemblances” is key to developing better vaccines and new drug treatments.

There are many cases in which efforts to stop one pathogen can help us fight its close relatives. For example, when mpox began spreading across North America back in 2022, scientists at LJI worked quickly to investigate vaccine strategies. They found that a vaccine originally designed to stop smallpox would likely also teach our T cells to combat the closely related mpox.

Our mission: Fight entire families of pathogens

LJI scientists are investigating how the immune system fights different members of the same family of pathogens. Spotting these “family resemblances” is key to developing better vaccines and new drug treatments.

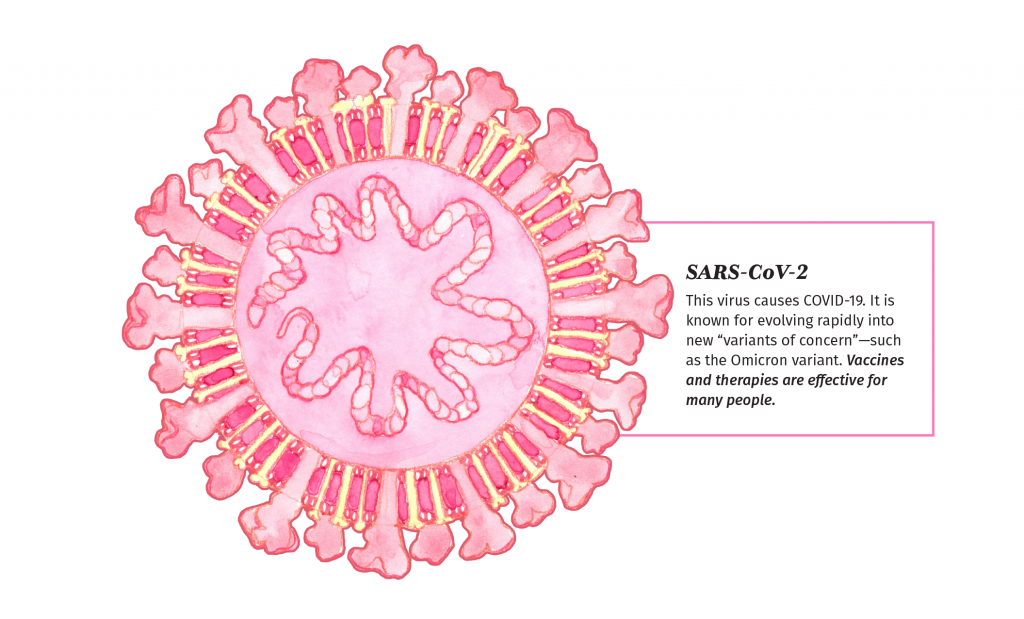

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of this research. Since 2020, LJI researchers have found that human immune cells can target vulnerable spots that many coronaviruses have in common. This discovery led LJI scientists to pursue “pan-coronavirus” vaccines to protect people from SARS-CoV-2 variants and future coronaviruses with pandemic potential.

Today, LJI researchers are pioneering efforts to train immune cells to fight dengue virus, Zika virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus with a single “pan-flavivirus” vaccine.

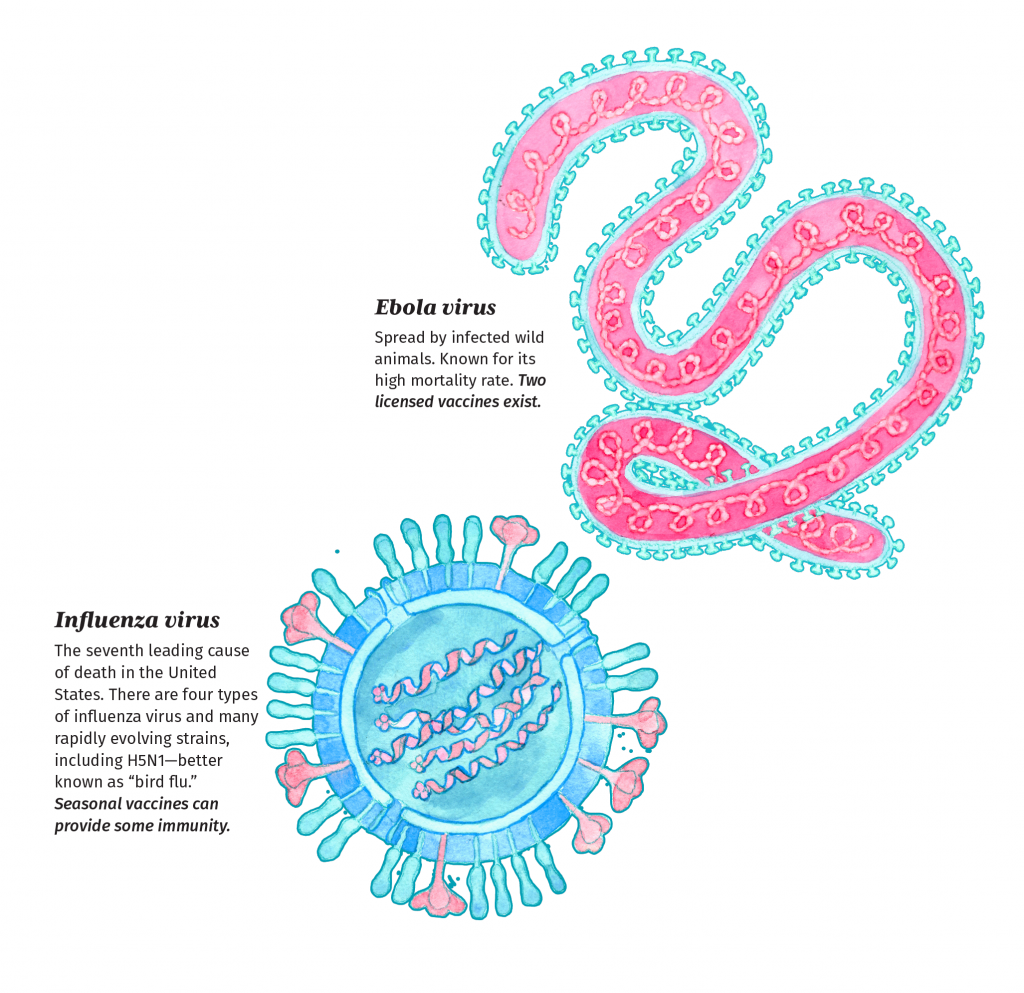

They have also found clues to developing a “pan-ebolavirus” vaccine to fight Ebola virus, Bundibugyo ebolavirus, and other deadly relatives.

LJI scientists are building a strong foundation for stopping future pandemics. If, one day, a new threat emerges—one we’ve never seen before—LJI is prepared to help save lives around the world.

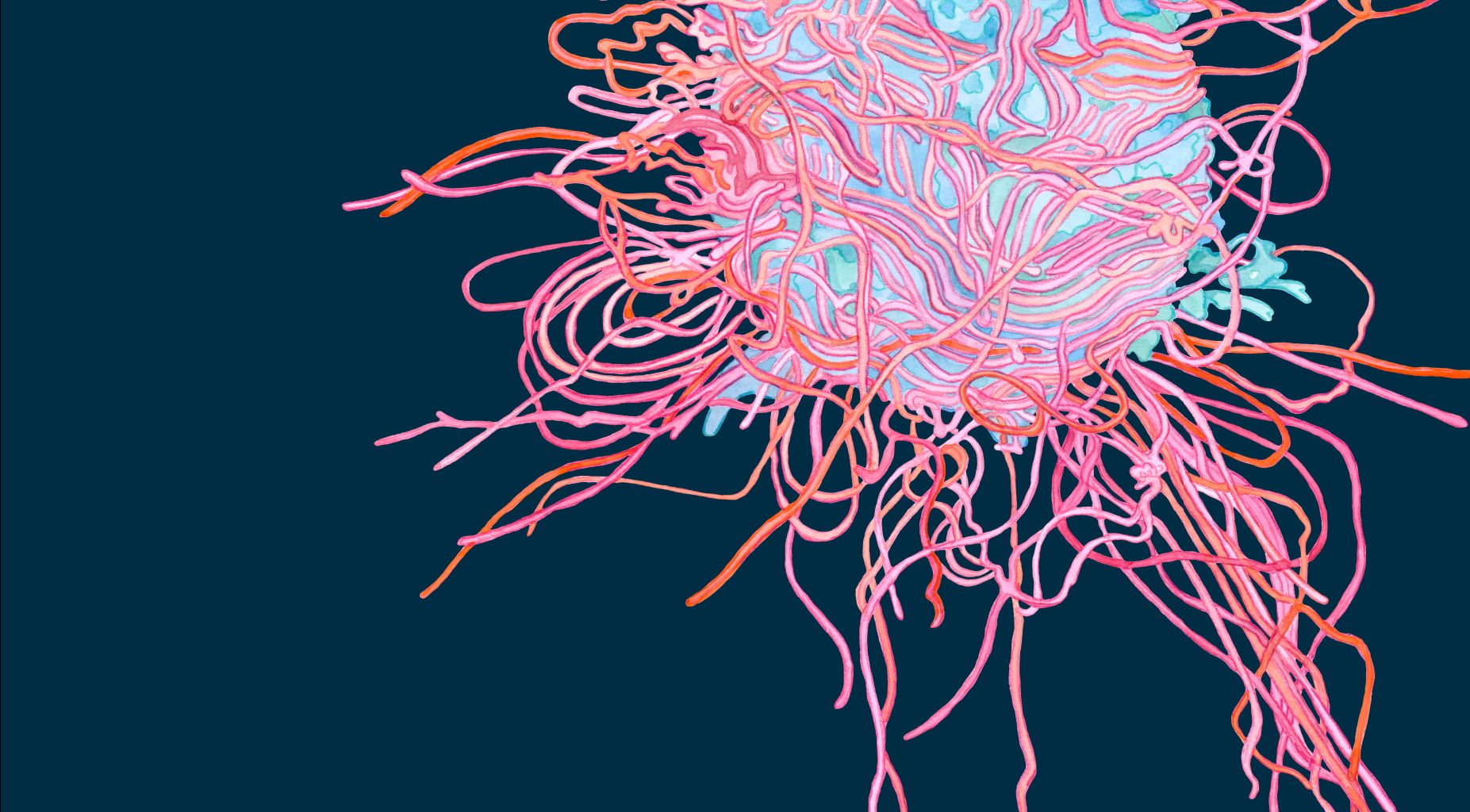

About the artist

This issue’s cover art and infographic illustrations were completed by San Diego artist Patricia Pauchnick. Pauchnick specializes in paintings, drawings, textiles, and ceramics that explore Southwestern history, land use, and urban/suburban development, as well as societal and natural borders. See more at patriciapauchnick.com.

The watercolor painting at the top of this article depicts Ebola virus (red and pink filaments) attacking a host cell (in blue).