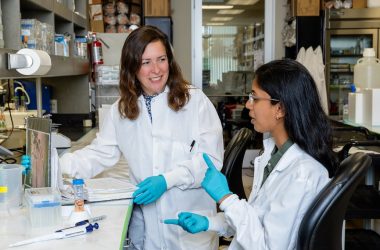

The pace of research for La Jolla Institute for Immunology’s Coronavirus Task Force is intense. Samples come in, data come out. Some labs are running 24-7. LJI scientists have brought us closer to ending the pandemic. They’ve also missed months of family dinners and bedtime stories. Missed sleep. Missed the before days.

This is the story—in the researchers’ own words—of how LJI’s dedicated scientists took on COVID-19.

LJI Research Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D.

January and February: A virus at the doorstep

Sydney Ramirez, M.D., Ph.D., Postdoctoral Researcher: My daughter, who is nine, was watching the evening news about the cases occurring in China. I think this was in December of 2019. She was scared.

Professor Lynn Hedrick, Ph.D.: When they shut down that area of China, we realized this was going to be a major issue if the virus escaped.

Professor Erica Ollmann Saphire, Ph.D.: We started thinking very seriously about the scientific questions that needed to be answered.

Instructor Alba Grifoni, Ph.D.: We started working on COVID-19 fairly early, around mid-January. I started doing bioinformatic analysis with Alessandro Sette and Bjoern Peters. I found that thrilling because the sequence of the virus had just come out. We were trying to predict which portions of the virus would be relevant for B cell and T cell responses.

Professor Bjoern Peters, Ph.D.: As part of the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) mission, we routinely create meta analyses of new data for pathogens out there. We did this before for Zika. We did that for the novel coronavirus. That was our first scientific response.

Dr. Grifoni: We were doing analyses day and night. That’s how we ended up publishing the Cell Host & Microbe paper in early March.

Professor Alessandro Sette, Dr. Biol. Sci.: The reason we got such a head start is because, based on completion of bioinformatic analysis, we were able to synthesize the peptides used to detect immune system responses to SARS-CoV-2.

Dr. Ramirez: Then there started to be reports of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic individuals spreading the virus. The screening and containment strategies that were successful for SARS would not be successful with COVID-19.

Dr. Jose Angel Regla Nava, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Researcher: The difference for this virus, in my opinion, was the facility for transmission from person to person. That’s how it got around the world so quickly. In only about five months, five million people in the world were positive.

By February, the Gates Foundation had approached Dr. Saphire to lead the Coronavirus Immunotherapy Consortium (CoVIC), a global effort to analyze virus-fighting antibodies. The National Institutes of Health required all companies wanting to participate in American clinical trials to first have their antibodies vetted by CoVIC at LJI.

March: Full speed ahead

Jason Greenbaum, Ph.D., Director, Bioinformatics: Around the second week of March—the Wednesday night when the President got on TV to address the nation. That’s when it started to get scary. The next day I asked all my staff to go home, because it seemed like it was getting worse.

Professor Shane Crotty, Ph.D.: This pandemic was not a surprise. I started my lab for this reason. It was apparent to virologists and plenty of vaccine researchers that emerging diseases are one of the few things that pose existential threats to the species.

Dr. Ramirez: I had been meeting with Shane regarding joining his lab in July. I met with him on a Wednesday in March just before the plans for the shutdown. He asked me if I was ready to commit to the lab, and I said that I was. Just two days later, I was rushing to get badge access to LJI before the planned shutdown that coming Monday.

The lab had only a skeleton crew due to the shutdown. Things picked up quickly, and other members of the lab were called in to help with the research. We started to collect more patient samples for analysis. Then it was full speed ahead.

Dr. Crotty: Everything we’ve been working on in the HIV vaccine community for the last 10 plus years, the tools and technologies to try to solve problems and move quickly, were immediately applicable to COVID-19—for studying the disease and for vaccine development.

Dr. Regla Nava: We used social distance. We stayed six feet from each other. In some labs, people worked in the morning or the afternoon and some at night.

Dr. Jose Angel Regla Nava, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Researcher

Sharon Schendel, Ph.D., Program Manager, CoVIC: We had people who were even working from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m.

Dr. Greenbaum: The novel coronavirus didn’t just change what I was working on—it was all that I was working on.

Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand, M.D. Ph.D.: We were already actively analyzing T cells reacting to different viruses using single-cell genomic approaches. In fact, we were examining T cells that react to a wide-range of respiratory viruses—so as COVID-19 spread, we were fully equipped to immediately understand the nature of SARS-CoV-2 reactive T cells.

Jennifer Dan, M.D., Ph.D., Clinical Associate: I was helping with the processing of blood specimens, but mainly I was running a lot of ELISAs [a blood testing technique] looking at anti-COVID responses.

Dr. Crotty: I was living in my office basically seven days a week. Analyzing COVID-19 patient data, figuring out experiment plans, and coordinating people. To figure out, as quickly as we could, what are the basic outlines of immune responses for COVID-19 patients.

Professor Sujan Shresta, Ph.D.: All of us were doing this research without dedicated funding, as it can take several months to get a new NIH grant. Time was of the essence and we just didn’t have the luxury to wait for slower funding channels with this viral infection. As we creatively juggled resources to respond quickly to the pandemic, donors played—and still play—a tremendously important role, allowing us to quickly initiate and sustain COVID programs until labs can receive a new round of NIH grants.

Dr. Saphire: Our job is to do the science we need to do to get humanity out of this. You have to hold it together and focus on that while the world goes crazy around you.

Instructor Kathryn Hastie, Ph.D.: Antibody discovery is a new research avenue in our lab and we are pioneering new ways to get as much information from each cell as possible—and as quickly as possible. Just before the pandemic, we were starting to think of how to take the immune system’s memory cells, which are of low abundance in blood samples, differentiate them into plasma cells that might secrete antibodies and then identify the individual cells and their targets in a day rather than weeks.

We wanted to do this with our African samples for Ebola antibody discovery and Lassa discovery. So I just sort of changed lanes again and started working with coronavirus samples.

Kristen Valentine, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Fellow: The scientific community really worked together. We started using several animal models—several mouse strains—to study T cell responses. We didn’t know how long we would have immunity after infection. This disease had only been around for a few months. We needed time.

Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D., Research Assistant Professor: You ran on adrenaline during those times, so you didn’t even feel the long hours that much. Most of the time.

By late March, LJI researchers had formed the LJI Coronavirus Task Force. The Institute had quickly become a hub for COVID-19 efforts.

April and May: New discoveries and new hope

Dr. Weiskopf: By April, we had established a collaboration with UC San Diego, and they helped us collect samples from some of the people who had been exposed and recovered.

Dr. Grifoni: We needed to see if how we predicted the immune system would respond to the virus would actually work in samples.

Dr. Peters: We needed to know—if you have a certain immune response prior to exposure to the virus, does that make you less likely to develop symptoms? And then how does your immune response look after you are exposed?

Dr. Ramirez: Our Cell manuscript showed that the individuals who had recovered from mild COVID-19 formed antibodies and helper T cell responses to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and other portions of the virus, called antigens. It suggested that the majority of individuals who recover from COVID-19 will have formed an immune response specific to the virus.

All of these individuals responded to the viral spike protein. This is the protein being used in the majority of candidate vaccines, so it seems as though these vaccines may result in

a similar response.

Dr. Sette: The Cell paper also clearly showed that, unexpectedly, people that had never seen the virus had preexisting immune reactivity to SARS-CoV-2.

Dr. Weiskopf: We realized that T cells recognize the entire virus and not just a certain protein. That was definitely important to know for therapeutics and vaccine development.

Dr. Shresta: We need to better understand how this one virus causes such a wide spectrum of symptoms. We also need to understand what makes it different from its closely related cousin, SARS, which causes severe symptoms in almost every patient. One ongoing approach is to conduct natural history studies in diverse populations, geographic locations, climatic zones—so that we understand the true epidemiology of this viral infection, including the impact of co-infections and diverse patient histories on the course of COVID-19.

My lab decided to study SARS-CoV-2 infection in Nepal. The major advantage is that I’m from there, so it’s easy to navigate that world. The size of the country makes it easy to conduct our studies, and South Asia is really important to study because it houses a quarter of the world’s population. The virus-host interaction may be different in clinical specimens in that part of the world.

Summer: And the work went on

Members of the Coronavirus Task Force published paper after paper over the summer. Dr. Saphire’s lab studied how mutations changed the virus and began a pilot study to test antibodies in precious human samples.

Dr. Hastie: We had to jump in with two feet. You can do all the studies you can with less valuable samples, but eventually you just have to take what you’ve learned and see what happens in a real environment.

Dr. Sette: Our Science paper that came out in July showed that the preexisting reactivity against SARS-CoV-2 that we and others had detected was directly related to immune memory cross-reactive with the common cold coronaviruses.

As the summer went on and cases began rising again, Anthony Fauci, M.D., Director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, lauded the Sette and Crotty-led research in a Congressional hearing.

Article photos by Earnie Grafton