For Madeleine Lopez, the pain started in the early morning. “I couldn’t straighten up, and when I stepped to get out of bed, it was like I was stepping on needles,” she remembers.

Then things got worse. “That night was when the fevers came,” says Lopez. She recalls changing her sweat-soaked sheet three times in the night.

Lopez has always been an active horse rider. She worked as a steward with the International Equestrian Federation, where she educated and guided horse-show participants through the rules of competition. Lopez is one of the best in the world. At the time, she was slated to serve as a steward at the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio.

This was no time to slow down. And yet, Lopez could barely walk. “Everything I touched, it hurt,” she says. “Even brushing my hair, brushing my teeth, hurt.”

Her doctor tested her for several viruses. The results showed that she was infected with Chikungunya (pronounced chick-kun-goon-yuh) virus, a mosquito-transmitted pathogen. Lopez was born and raised in Puerto Rico, and she was living there when her illness began. But it’s impossible to know exactly where she contracted the virus. Her work as a steward took her all across Central and South America — regions where mosquito-borne viruses such as Zika, dengue, and Chikungunya are transmitted.

There aren’t any antiviral treatments available for Chikungunya. Lopez’s life came to a halt. Her doctor tried to help by flooding her system with vitamin C and a traditional tea meant to soothe inflammation. “They kept me like that for six months,” says Lopez.

When a virus doesn’t act like a virus

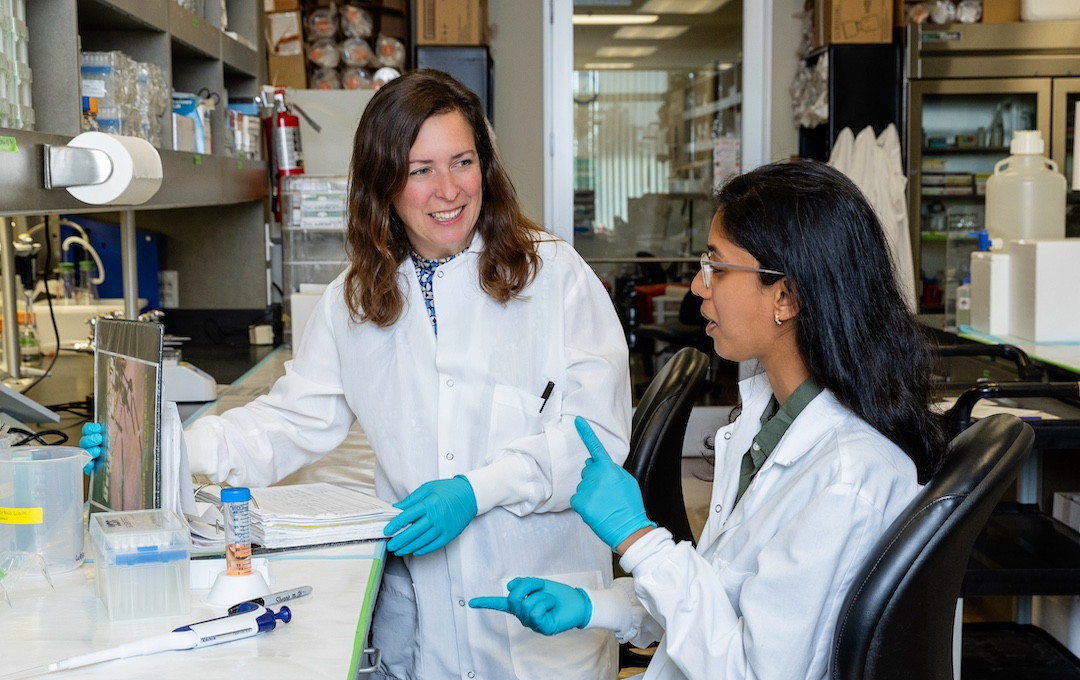

La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D., wanted to know how a mosquito could cause autoimmune disease. Or at least what sounds a lot like autoimmune disease.

Weiskopf is an expert on how the immune system’s T cells combat viral threats, such as dengue virus and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Her research has helped reveal the importance of recruiting T cells — not just antibody-producing B cells — to prevent severe viral infections.

T cells are great at stopping infections, but T cells can also attack a person’s healthy tissues by accident. This kind of self-attack can lead to harmful inflammation and autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

There are some cases where viral infections appear to trigger the development of an autoimmune disease later on. For example, scientists have found hints that Epstein-Barr virus infection may be associated with multiple sclerosis and lupus. But these associations are rare. Or at least they are very, very hard to spot.

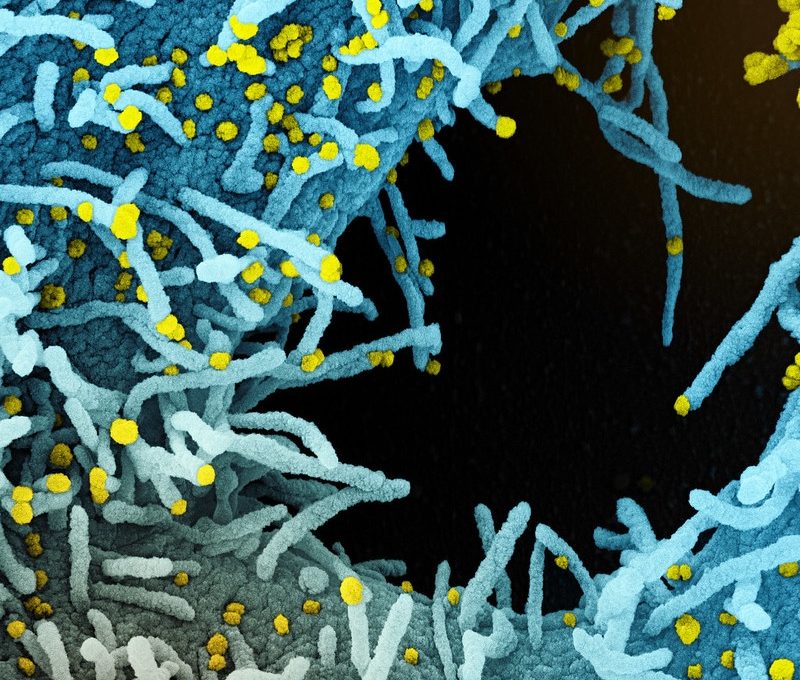

A few years ago, Dr. Weiskopf saw something strange happening in cases of Chikungunya virus infection. Chikungunya virus is increasingly common in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Chikungunya infection tends to start with symptoms such as a fever, headache, and body aches. The disease usually clears up fairly quickly, but in rare cases, it can be fatal.

Chikungunya also leaves some of its victims with chronic, debilitating joint pain. This joint pain comes with bone erosion and cartilage damage, symptoms more commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis — an autoimmune disease.

This joint pain is weird because it primarily strikes women.

Dr. Weiskopf is investigating this surprising sex-based difference. Her work so far has shed light on T-cell activity that blurs the line between antiviral responses and autoimmunity.

Patients carry key clues

Dr. Weiskopf started with a surprising clue found in blood samples from Chikungunya patients in South America. In these samples, Dr. Weiskopf expected to see two main types of virus-fighting T cells: CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells.

Quickly, Dr. Weiskopf realized the CD8+ T cells were missing. “We were very surprised to find that no CD8+ T cells appeared to recognize the virus, which is uncommon for a viral infection,” says Dr. Weiskopf.

Many of the patients did have a strong CD4+ T cell response to Chikungunya virus. CD4+ T cells are part of an effective antiviral immune response. And yet — the levels and the cytokine profile of the CD4+ T cells more closely resembled the T cells that drive rheumatoid arthritis.

“Now, I’m an infectious disease researcher, but I could see that this T-cell response looked awfully like what we see in autoimmune disease,” says Dr. Weiskopf.

“Now, I’m an infectious disease researcher, but I could see that this T cell response looking awfully like what we see in autoimmune disease.”

– LJI Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D.

UC San Diego Graduate Student Rimjhim Agarwal, who is a member of the Weiskopf Lab, decided to take a closer look at patient demographics. Agarwal found that the majority of study participants with the strong CD4+ T-cell response were women in their 40s. These same women were also the most likely to develop chronic joint pain after dealing with Chikungunya.

Lopez knows how these women feel. Her doctor had no idea why a viral infection led to terrible joint pain. She’s known many people who have become infected with Chikungunya, dengue, and similar viruses. In her own family, she and her seven siblings have all dealt with these diseases. And yet she was the only one to develop joint pain—which led to permanent joint damage.

Why did Lopez develop these chronic symptoms following a viral infection? Was something different about her immune response?

After spending six months recuperating, Lopez did feel a lot better. Then, just before the Olympic Games in Rio, Lopez asked her doctor to take a look at her left knee. More bad news. The soft, stretchy cartilage in her knee was gone. Every step forced her to walk “bone on bone.” Her doctor urged her to get a knee replacement. She agreed—but not until after the Olympics.

Her knee replacement helped as much as it could, but Lopez has not fully recovered from her original illness. “It got complicated,” she says. “Some nerves never came back. I’ve lost feeling in my left toes and the bottom of my left foot.”

An ongoing search for answers

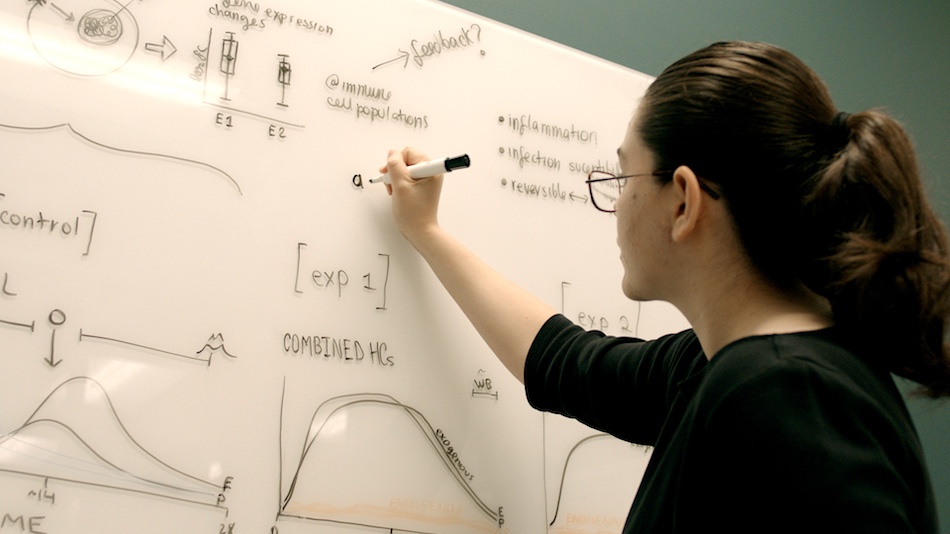

Dr. Weiskopf and Agarwal needed a clearer view of T cells.

Agarwal soon won support from The Tullie and Rickey Families SPARK Awards for Innovations in Immunology. For her project, funded through the generosity of the Rosemary Kraemer Raitt Foundation Trust, Agarwal launched a new study to figure out whether the joint pain patients experience after Chikungunya infection comes from a dangerous miscommunication in the immune system. Perhaps virus-fighting CD4+ T cells are mistaking joint tissue for a threat.

The findings of Agarwal’s Tullie and Rickey Families SPARK award project have led to ongoing research in the Weiskopf Lab and garnered attention from the wider research community. In May 2024, Agarwal was selected as a Major Symposium speaker for IMMUNOLOGY2024™, the 2024 Annual Meeting of the American Association of Immunologists (AAI). And in September 2024, Agarwal presented her data at a special National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) workshop on infections and autoimmune diseases.

“More and more people are realizing that viral infections can trigger autoimmune disease symptoms,” says Agarwal.

Dr. Weiskopf is interested in studying whether men and women are producing different types of CD4+ T cells during infection. Teasing apart this type of sex-based difference may be key to developing Chikungunya vaccines that recruit the right types of T cells to fight the virus.

“Chikungunya causes recurring outbreaks,” says Dr. Weiskopf. “We want to be prepared.”

Lopez remembers exactly what her doctor said when she was diagnosed. “He said there’s nothing we can do about it,” she recalls. Even now, more than a decade after her illness, there are still no specific therapies to treat Chikungunya, dengue fever, Zika virus disease, or many other mosquito-borne viral infections.

Lopez now has permanent damage in many of her joints. Her left side has been hit the hardest, and one of her fingers on her left hand has begun to rotate—developing the familiar twist of rheumatoid arthritis.

“I don’t know why it happened. Whether it will come back? I don’t know,” says Lopez. “I wouldn’t wish that for anybody.”

UPDATE

In July 2025, Dr. Weiskopf published the first-ever map of which parts of Chikungunya virus trigger the strongest response from the body’s T cells.

With this map in hand, researchers are closer to developing Chikungunya vaccines or therapies that harness T cells to strike specific targets, or “epitopes,” to halt infection. The new study also offers important clues for understanding why many people experience chronic, severe joint pain for years after clearing the virus.

“Now we can see what T cells are seeing patients with chronic disease,” says Dr. Weiskopf.

Now the question is—why do these T cells stick around to cause inflammation in some but not all people? Dr. Weiskopf and Agarwal are now looking at where Chikungunya virus might hide in the body to stimulate a long-term T cell response.

The LJI team also hopes to help other laboratories shed light on how to fight the virus. “Identifying the immunodominant T cell epitopes could seed new research into Chikungunya-specific T cell responses,” says Agarwal.