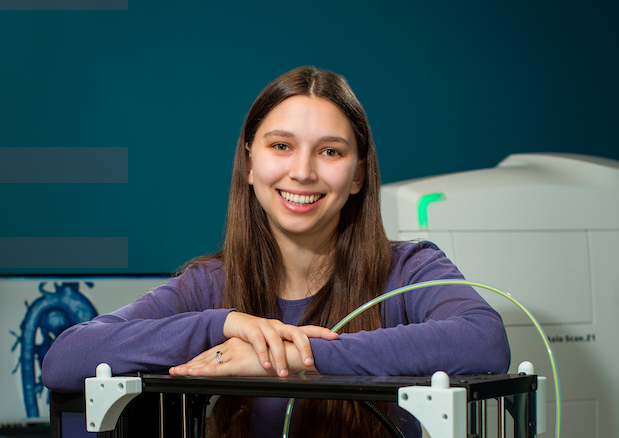

Considered the top type 1 diabetes expert in the world, Matthias von Herrath, M.D., feels equally at home in academia and big pharma.

When Novo Nordisk, a global pharmaceutical company headquartered in Denmark and best known for its diabetes products, wanted to reinvigorate its type 1 diabetes (T1D) research program, it looked no further than La Jolla Institute (LJI). It was the work of LJI Professor Dr. Matthias von Herrath that had caught their attention.

A latecomer to biomedical research, the trained virologist was running an innovative and world-renowned research program on the pathology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes as part of the national Pancreatic Organ Donor network (nPOD). Dr. von Herrath accepted Novo Nordisk’s offer to head up the company’s new T1D research center in Seattle on one condition: He would keep his lab at LJI. Realizing the potential benefits of having closer interactions with a big pharma company, LJI agreed to the joint appointment, which is atypical in academic organizations.

Born and raised in Germany, Dr. von Herrath received his M.D. from the University of Freiburg and spent several years working in infectious diseases, internal medicine, and intensive care before his passion for bench research brought him to San Diego. Inspired by his patients, many of whom struggled with type 1 diabetes, Dr. von Herrath founded the Center for Type 1 Diabetes at La Jolla Institute and began studying the causes of the disease. “I got into type 1 diabetes research because I really thought it might be a problem that we can tackle in our lifetime,” he says.

What made the job offer from Novo Nordisk so appealing?

I always wanted to have an effective arm to get new treatments into the clinic. Clinical trials for type 1 diabetes are very expensive because of patient heterogeneity.

Can you explain?

The disease progresses at different speeds in different people and because of that the trials have to be bigger, which makes them very expensive. Going into big pharma was very purpose-driven with the main goal of catalyzing large clinical investigations and helping to develop new treatments.

Why did you decide to keep your lab at LJI?

You just cannot make drugs without a solid mechanistic and pathological understanding of the disease at hand. The fundamental research we do at LJI—trying to understand the pathology of type 1 and to a certain extent type 2 diabetes— lays the foundation for better therapeutics, which is super important. Without this basic, mechanistic research we would choose poor drug targets.

What’s the current thinking on the cause or causes of T1D?

We know that many different genes contribute to the disease but, in addition to the genetic predisposition , there’s a very strong environmental component.

What is known about the environmental factors that contribute to T1D?

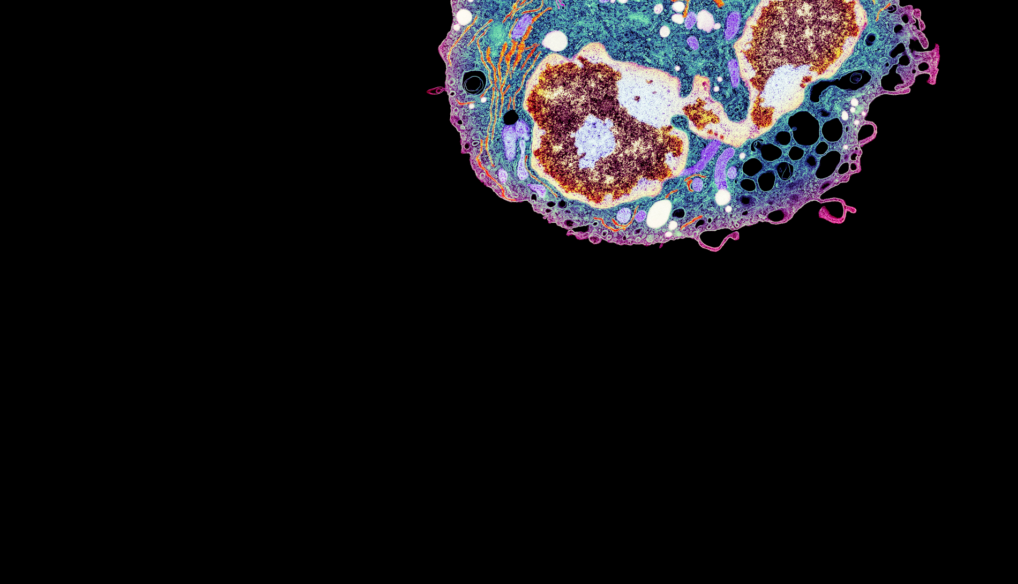

This is a very complex area and we don’t know enough to even begin to pinpoint what the cause may be. The environment probably works via the immune system and it is something we are working on quite extensively here at LJI. Ultimately, the immune system attacks and destroys beta cells and that’s why we ask what influences the visibility of the beta cell to the immune system. But we still don’t know why the immune system starts seeing beta cells.

Are there any clues as to what might be going on?

For one, there’s evidence that the response to viral infections may be altered in the islets of Langerhans, which are tiny clusters of cells scattered throughout the pancreas that contain the insulin-producing beta cells. It seems islet cells are hyper responsive. Understanding why would help us a great deal. It would also mean that it is not one particular virus but that it is a more general way of how beta cells as an organ respond to viruses in type 1 diabetes.

Are there any other factors?

There is also heterogeneity across the pancreas, which means that not all islets are affected the same way. That may have to do with the enervation of single islets, which signals the immune system some form of stress and that’s why certain areas of the pancreas become a target of the immune system.

How did becoming a member of the nPOD consortium impact your research?

Without the pancreatic organ donor consortium we wouldn’t be doing what we are doing. We were one of the first labs to use this incredible resource and it allowed me to switch the whole lab around to studying clinical pathology in humans, which is fundamental to understanding what’s actually happening in patients. Novo Nordisk acknowledged that this is really important work and agreed to let me continue basic research at LJI.

Between two jobs and a family, how do you find time to unwind?

I play violin. It puts good colors into my head and makes me feel relaxed.

Wait, what?

I see colors when I play music and every key has a different color. It’s called synesthesia. Playing music completely changes my mindset, it balances me, and keeps me sane. Riding my bike does the same thing. Usually, when I am done with my Novo Nordisk responsibilities in the morning—the headquarters are in Copenhagen and there is a nine-hour time difference—I take a bike ride or play some violin and then come to La Jolla Institute. That way I have a clear break in between and can refocus my mind on something else.

Many scientists are also accomplished musicians. Is there a connection?

That’s an interesting question but I don’t have a good answer. Both are creative endeavors but certain forms of music like playing in a band are more fun because you can write your own music and then see the sound coming together. When I play the violin I also like to put my own interpretation on pieces and that’s why I never enjoyed playing in an orchestra. I couldn’t express myself.

Have you ever considered becoming a professional musician?

As a teenager I thought about playing the violin professionally but quickly realized I wasn’t going to hack it.

Mostly because Anne-Sophie Mutter was born the day before I was born. We are from the same area, Germany’s Black Forest, and at the time she was very visible in Southern Germany. When she started recording with Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic I knew it wouldn’t work. I also played guitar for a very long time because I thought there was more creative freedom.

I came to the U.S. after working in intensive care oncology for several years for two reasons: To do research and to see what I could do with music. After one year we had a record offer from Arista Records and that’s as far as we pushed it.